Approximately 1.5 million people in the United States alone have IBD. The human and animal data which implicated MCs and their exocytosed mediators in the inflammation that occurs in the intestine and colon of patients with IBD are discussed in detail in our recent review (Hamilton et al., Inflam. Bowel Dis. J., 2014:20:2364) (view Hamilton et al.). Because patients with IBD have increased numbers of hTryptase‑β+ MCs in the gastrointestinal tract, we hypothesized in 2011 that mMCP-6, mMCP-7, and/or mPrss31 might have a prominent pro‑inflammatory roles in experimental colitis. Oral administration of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) or rectal administration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) results in an acute colitis in rodents that resembles certain aspects of IBD in humans. In the DSS model, damage to the colon’s epithelium results in increased mucosal permeability, thereby allowing harmful gut flora better access to the colon’s mucosal and submucosal layers. Activation of poorly defined immune pathways ultimately results in the extravasation of large numbers of peripheral blood neutrophils and other inflammatory cells into the colon, loss of epithelial cells and globlet cells, and proteolytic damage to the colon’s extracellular matrix. In the TNBS model, disruption of the epithelium by alcohol and subsequent haptenization of colonic proteins by TNBS results in transmural inflammation in the colon. The DSS- and TNBS-induced colitis models have given valuable insight as to the importance of colonic epithelial barrier function and the subsequent acute inflammatory response to injury and luminal antigens in the lower gastrointestinal tract.

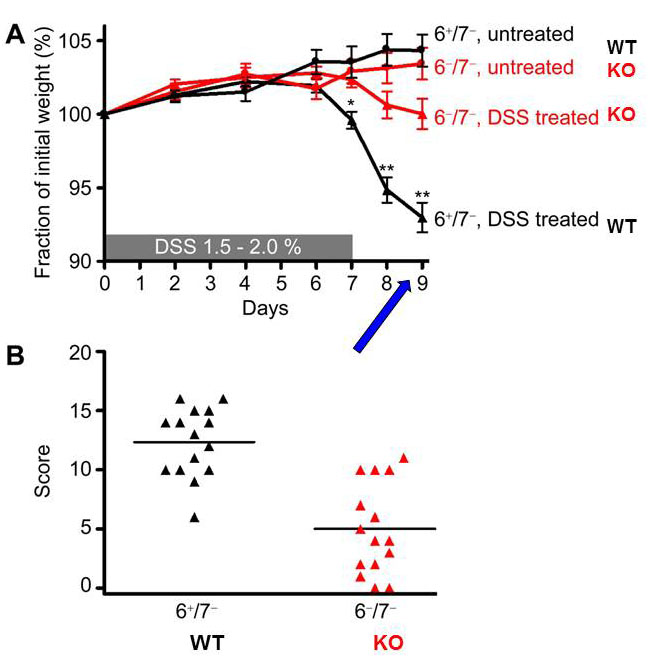

Fig. 9. Transgenic mice lacking the tetramer-forming tryptase mMCP-6 (6–/7–) are protected from dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis. (A) DSS-treated 6–/7– mice lost significantly less of their initial body weight than similarly treated WT mice by day 9. (B) Using a 20-point scoring system, DSS-treated mMCP-6-null mice also had significantly lower histopathology scores than the DSS-treated WT at day 9 (from Hamilton et al., PNAS 2011;108:290).

The DSS and TNBS colitis models were used by us to evaluate the differences between mouse lines that differ in their expression of the three tryptases expressed in MCs with regard to weight loss, colon histopathology, and endoscopy scores. Microarray analyses were performed, and confirmatory real-time polymerase chain reaction, ELISA, and/or immunohistochemical analyses were carried out on a number of differentially expressed cytokines, chemokines, and MMPs.

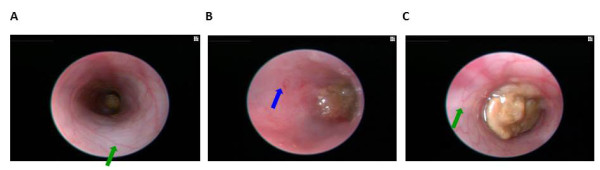

Fig. 10. Colonoscopy of an untreated WT B6 mouse (A, also see video 1), a DSS-treated WT B6 mouse (B, also see video 2), and a DSS-treated mMCP-6-null B6 mouse (C, also see video 3). The mucosal surface of the untreated WT B6 mouse is smooth, and its underlining blood vessels can be readily seen (green arrow). In contrast, the blood vessels of the wild‑type B6 mouse that received DSS for 5 days were less visible due to the submucosal edema (blue arrow). Ulcers also were present in this DSS-treated animal. The mucosal surface of the DSS-treated mMCP-6-null B6 mouse was similar to that of the untreated WT mouse (green arrow). The light brown matter in the center of the colons are feces (from Hamilton et al., PNAS 2011;108:290).

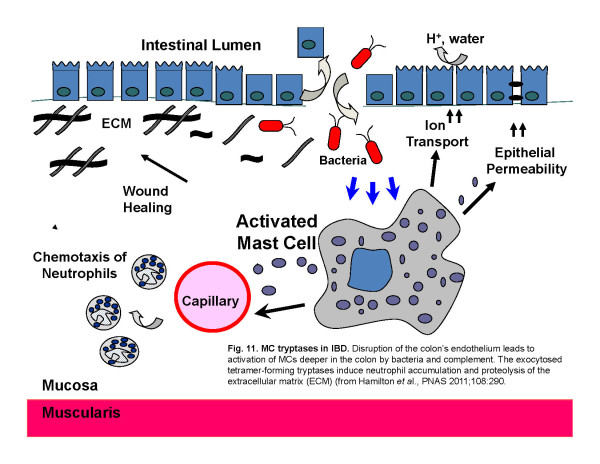

mMCP-6-null mice (Hamilton et al.,Proc. Natl. Acad Sci USA 2011;108:290) (view Hamilton et al.) and mPrss31-null mice (Hansbro-Hamilton et al., J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:18214) (view Hansbro-Hamilton et al.) that had been exposed to DSS had significantly less weight loss and significantly lower pathology and endoscopy scores than similarly-treated WT mice (see Figures 9-11 and Videos 1-3). The difference in colitis severity was confirmed endoscopically in TNBS-treated mice. Evaluation of the distal colon segments revealed that numerous pro‑inflammatory cytokines, chemokines that preferentially attract neutrophils, and MMPs that participate in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix were all markedly increased in the colons of DSS-treated WT mice relative to untreated WT mice and DSS-treated mMCP-6-null mice. Collectively, our data revealed that mMCP‑6 and mPrss31 are essential MC-restricted mediators in chemically-induced colitis in mice, and that these tryptases act upstream of many of the factors implicated in IBD in humans. Our mouse data therefore raise the possibility that their human orthologs have similar adverse roles in patients with ulcerative colitis and/or Crohn’s disease.

Fig. 11. MC tryptases in IBD. Disruption of the colon’s endothelium leads to activation of MCs deeper in the colon by bacteria and complement. The exocytosed tetramer-forming tryptases induce neutrophil accumulation and proteolysis of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (from Hamilton et al., PNAS 2011;108:290).

Whatever mechanisms are operative in tryptase-dependent inflammation, it is now apparent that one must knock out at least two of the three tryptase genes in MCs to undercover the prominent adverse activities of this family of serine proteases in experimental colitis. Since human MCs express three functionally similar tryptases encoded by the corresponding TPSAB1, TPSB2, and TPSG1 genes, it is likely that the primary reason why the tryptase locus on human chromosome 16p13.3 had not been identified in varied genome wide association studies of patients with COPD or another inflammatory bowel disease is because of the redundancy of this family of MC-restricted serine proteases.

Major advances have been made in our understanding of the causes of IBD. Although numerous susceptibility genes have been identified, exposure to cigarette smoke confers the greatest risk for developing Crohn’s disease. We are therefore are presently evaluating whether or not our cigarette smoke induced COPD model (view Beckett et al.) also leads to symptoms in the gastrointestinal tracts of WT mice (but not in our tryptase-null mouse strains) that resemble those in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Comments are closed.